by Jon:

I'm going to skip the "Severed Thumbs" review on this one because my colleague Mr. Gattanella best summed up my thoughts on the movie in his review. This is more of a critique on what Aronofsky did effectively to utterly terrify me. Black Swan is the most effective psych. thriller that I have seen in a long time. This is not just the director's use of the visuals and effects but how it built up to that final clash of insanity that led me to think twice about turning off the lights before I went to sleep. In the movie there are very little touches that the viewer is introduced to that, if one blinks, will miss. Whenever the movie is from the point of view of Nina, the audience is slowly introduced to her madness which gives a much more visceral effect. In short, you are losing your mind at the same rate Nina is. The effects were second to the timing, when Nina is cutting her nails, you feel like you're cutting your nails too. When she slips and cuts her finger, you feel your finger getting cut, when Nina hallucinates you question your own view of reality. This causes the inevitability of the film's climax. The viewer saw it coming as Nina did, but there was nothing anyone could do about it, and that feeling of being utterly powerless is where the true terror comes from.

Sunday, December 19, 2010

Sunday, December 12, 2010

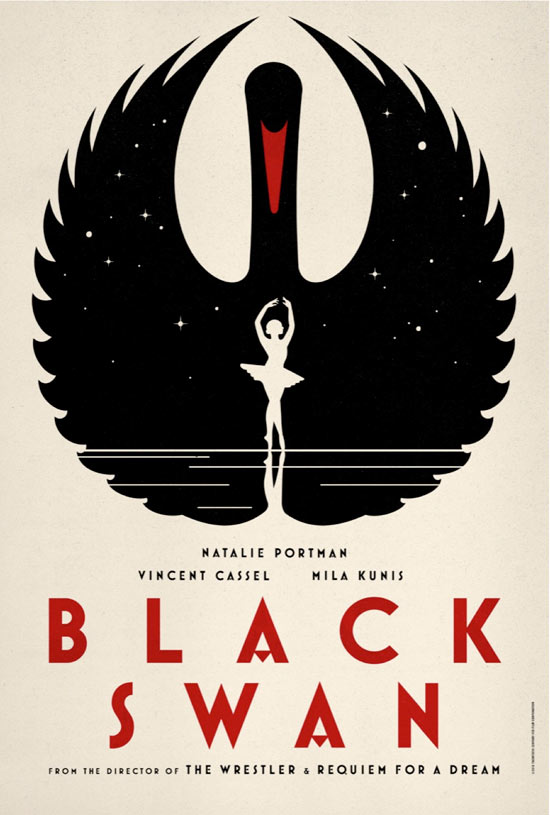

Black Swan, or long live the new feathers

Hey guys, Jack here:

"Just because you're a perfectionist doesn't mean your perfect."

(Jack Nicholson to Stanley Kubrick on the set of The Shining)

The world of the ballet is tough, hard and cruel to the body. It should be a given as soon as you hear the name Darren Aronofsky as director of this film Black Swan, and that his previous film was The Wrestler, that he would be obsessed with that aspect of it. Then again, obsession is one of the main deals to an Aronofsky movie: the perfect number in Pi, fame and achieving good life with no worries in Requiem for a Dream; finding a cure in The Fountain; one's identity in The Wrestler. Every character has a drive, usually towards self-destruction, and the body, the flesh and the spirit sometimes one or the other or both vying for attention, becomes an excrutating focual point.

But hey, you didn't come here to get a full-on breakdown of Aronofsky as auteur did you? No, maybe you did (sorry for the lapse into really addressing at *you* in this review, I'll stop now, maybe). In Black Swan we get Aronofsky's talents at a high peak. It's about a world where pressure cooks the soul and the drive has to be kept again (clap) again (clap) AGAIN (clap). The ballerina is no less an athlete or professional body-fucker-upper than a wrestler, only with this it's the feet, the toes, and the constitution of the body weight. Natalie Portman, for example for the role, lost twenty pounds off of her already skinny frame to play the role (it's not The Machinist but it'll do). And Aronofsky's aim is to explore the nature of a perfectionist in this realm, or someone driven to be one after so many years, and how it drives one mad. Kubrick might be proud.

What's fascinating about Nina Sayers (Portman) is how much she creates her own sense of must-be-perfect-self-worth once she gets the role of the black swan along with the white swan. The latter is just fine, she's a delicate flower of a young woman able to portray her fragile veneer. The former is more difficult, as she's not impulsive, or very sexual. If one reads into ber backstory she's probably like the result of a parent who drove her to this as a child, maybe a very young one, as Nina's mother (Barbara Hershey) tells her she's been at this ballet thing for a long time. She's not even thirty and already becoming an old-timer; she's replacing "The Dying Swan" herself, Beth McIntyre (Winona Ryder, one of her best performances, seriously, even in such a short capacity she amazes in a one 1/2 note performance).

(Oh, by the by, 'Dying Swan' isn't merely a reading-into kind of deal. On IMDb, unknown to me when I saw the movie, characters are listed with monikers; Nina is the "Swan Queen", her would-be friend and rival newcomer Lily (sexually charged and loosely played Mila Kunis) is the "Black Swan", and the trainer, Thomas Leroy (Vincent Cassel, kind of sinisterly hamming it up as a descendant of a character originally played with more class by Anton Walbrook in The Red Shoes) is the "The Gentleman" weirdly (or ironically) enough. The mother is the "The Queen". Perphaps these are references to the Swan Lake ballet. Or maybe Aronofsky's just being cute, or having fun in his own diabolical-dark way).

What happens to Nina isn't quite so sudden; from the start of the movie there's a sense of paranoia to her, of a sound she may hear (thanks sound fx!) or a dark figure standing down a corridor at the ballet studio. Once she gets this dual role and is pushed on by her instructor/mentor/sexual-assaulter Thomas to dig deeper to find that wild-side for the black swan, which isn't easy to find, she goes deeper into a mania where it is hard to separate reality from fantasy. From nightmare, in fact. Compounding this are the diametrically opposed forces of Nina's Mother, who once had dreams of her own and failed to achieve them (like a lot of showbiz mums), and her equal love/disdain relationship with her. One of the more interesting scenes psychologically comes when after Nina got the two roles, and her mother gets her a cake. Nina turns it down, saying her stomach "is still in knots." Queen Sayers doesn't take this lightly and makes a dramatic pose to throw out the whole thing altogether. Nina relents, and has a piece. Whew.

One may think back for comparison to Aronofsky's own Requiem for a Dream, where we had a trippin-balls Ellen Burstyn imagining a living-bouncing refrigerator was coming her way in her apartment. I might think back more to classic-horror period Cronenberg, where one saw James Woods push a gun into his stomach and then attach itself to his hand in Videodrome. The flesh can be an icky, dicey and really squirm-worthy thing (one still can't quite get over the arm-off in 127 Hours last month), and Aronofsky pushes this right from the start.

When he shows these ballerinas working their toes into submission, and having to push their ankles and feet to a limit, it's not just a "showing the profession" kind of deal. It's connected to what Nina goes through later with her "other" condition, of an unusual mark on her back that goes in a straight line and is red, and perhaps scratched. Other people (at least Nina's mother) notice it on her, but Nina is the only one who sees it extend to its logical destination. When it gets there- and dear reader, you'll know where- its a transformation not unlike Mystique in the X-Men (side note, Aronofsky - The Wolverine - awesome).

A body can be a thing that can waste away, but the mind is a bit more complicated, and the subjective perspective is something Aronofsky is masterful at portraying here. I was completely caught up with Nina about midway through the film. Her mania became my mania in a way; Aronofsky's choices of close-ups on this woman falling apart is a distinct and maybe (only) brave choice to do. She has fear, anguish, pain, delirium, occasionally (when a 'substance' is put in her drink by Lily) euphoria, and finally full-on homicidal madness. I couldn't discern reality from fantasy in this film, which is something that excites me and surprises me. That it's also in the framework of a full-borne melodrama is something that excites further. No, it's not quite The Red Shoes. It's something different, adaptive, as if Stephen King with a refound lust for glory took the Red Shoes and doused it in kerosene and made it dance till it passed out. It's script, which deals in conventions, is deceptive once its truer purposes are revealed by its director (who, admittedly, rises it up from potential pitfalls that backstage-dramas can have).

Casting is so important though, outside of a director's vision, and Aronofsky has a lead here that could equal her previous Randy 'The Ram' from The Wrestler. Natalie Portman seems to find a really strong role every five years or so, and this is one of them. In Nina she finds darker countours than I've seen her play before, and as the filmmaking reaches a feverish pitch the actress is right there along for the ride. I mentioned close-ups before (as did Jim Emerson in his blurb, bless him), and Portman is game to fill up the frame with her availability and horror that she can give as an actress. It's a revelatory performance in that she runs a gamut of emotional notes from tender to sad to hysterical to mad to evil and just downright... determined. That she's also an amazing ballerina should be a given to be in this film, though her dedication to the role pays off in that climactic Swan Lake performance. It's not all visual fx up there and lighting daring-do. It's flesh and blood and eyes turned red and wings flapping like daggers.

Did I mention the music? Or the cinematography? Or any number of things? In short, it's one of the best of the year, do go see it if it's around the area or when it opens wider this Christmas. As far as head-trip mind-fuckers go, it's the director's finest and, within its cozy hand-held 16mm confines, most ambitious work.

"Just because you're a perfectionist doesn't mean your perfect."

(Jack Nicholson to Stanley Kubrick on the set of The Shining)

The world of the ballet is tough, hard and cruel to the body. It should be a given as soon as you hear the name Darren Aronofsky as director of this film Black Swan, and that his previous film was The Wrestler, that he would be obsessed with that aspect of it. Then again, obsession is one of the main deals to an Aronofsky movie: the perfect number in Pi, fame and achieving good life with no worries in Requiem for a Dream; finding a cure in The Fountain; one's identity in The Wrestler. Every character has a drive, usually towards self-destruction, and the body, the flesh and the spirit sometimes one or the other or both vying for attention, becomes an excrutating focual point.

But hey, you didn't come here to get a full-on breakdown of Aronofsky as auteur did you? No, maybe you did (sorry for the lapse into really addressing at *you* in this review, I'll stop now, maybe). In Black Swan we get Aronofsky's talents at a high peak. It's about a world where pressure cooks the soul and the drive has to be kept again (clap) again (clap) AGAIN (clap). The ballerina is no less an athlete or professional body-fucker-upper than a wrestler, only with this it's the feet, the toes, and the constitution of the body weight. Natalie Portman, for example for the role, lost twenty pounds off of her already skinny frame to play the role (it's not The Machinist but it'll do). And Aronofsky's aim is to explore the nature of a perfectionist in this realm, or someone driven to be one after so many years, and how it drives one mad. Kubrick might be proud.

What's fascinating about Nina Sayers (Portman) is how much she creates her own sense of must-be-perfect-self-worth once she gets the role of the black swan along with the white swan. The latter is just fine, she's a delicate flower of a young woman able to portray her fragile veneer. The former is more difficult, as she's not impulsive, or very sexual. If one reads into ber backstory she's probably like the result of a parent who drove her to this as a child, maybe a very young one, as Nina's mother (Barbara Hershey) tells her she's been at this ballet thing for a long time. She's not even thirty and already becoming an old-timer; she's replacing "The Dying Swan" herself, Beth McIntyre (Winona Ryder, one of her best performances, seriously, even in such a short capacity she amazes in a one 1/2 note performance).

(Oh, by the by, 'Dying Swan' isn't merely a reading-into kind of deal. On IMDb, unknown to me when I saw the movie, characters are listed with monikers; Nina is the "Swan Queen", her would-be friend and rival newcomer Lily (sexually charged and loosely played Mila Kunis) is the "Black Swan", and the trainer, Thomas Leroy (Vincent Cassel, kind of sinisterly hamming it up as a descendant of a character originally played with more class by Anton Walbrook in The Red Shoes) is the "The Gentleman" weirdly (or ironically) enough. The mother is the "The Queen". Perphaps these are references to the Swan Lake ballet. Or maybe Aronofsky's just being cute, or having fun in his own diabolical-dark way).

What happens to Nina isn't quite so sudden; from the start of the movie there's a sense of paranoia to her, of a sound she may hear (thanks sound fx!) or a dark figure standing down a corridor at the ballet studio. Once she gets this dual role and is pushed on by her instructor/mentor/sexual-assaulter Thomas to dig deeper to find that wild-side for the black swan, which isn't easy to find, she goes deeper into a mania where it is hard to separate reality from fantasy. From nightmare, in fact. Compounding this are the diametrically opposed forces of Nina's Mother, who once had dreams of her own and failed to achieve them (like a lot of showbiz mums), and her equal love/disdain relationship with her. One of the more interesting scenes psychologically comes when after Nina got the two roles, and her mother gets her a cake. Nina turns it down, saying her stomach "is still in knots." Queen Sayers doesn't take this lightly and makes a dramatic pose to throw out the whole thing altogether. Nina relents, and has a piece. Whew.

One may think back for comparison to Aronofsky's own Requiem for a Dream, where we had a trippin-balls Ellen Burstyn imagining a living-bouncing refrigerator was coming her way in her apartment. I might think back more to classic-horror period Cronenberg, where one saw James Woods push a gun into his stomach and then attach itself to his hand in Videodrome. The flesh can be an icky, dicey and really squirm-worthy thing (one still can't quite get over the arm-off in 127 Hours last month), and Aronofsky pushes this right from the start.

When he shows these ballerinas working their toes into submission, and having to push their ankles and feet to a limit, it's not just a "showing the profession" kind of deal. It's connected to what Nina goes through later with her "other" condition, of an unusual mark on her back that goes in a straight line and is red, and perhaps scratched. Other people (at least Nina's mother) notice it on her, but Nina is the only one who sees it extend to its logical destination. When it gets there- and dear reader, you'll know where- its a transformation not unlike Mystique in the X-Men (side note, Aronofsky - The Wolverine - awesome).

A body can be a thing that can waste away, but the mind is a bit more complicated, and the subjective perspective is something Aronofsky is masterful at portraying here. I was completely caught up with Nina about midway through the film. Her mania became my mania in a way; Aronofsky's choices of close-ups on this woman falling apart is a distinct and maybe (only) brave choice to do. She has fear, anguish, pain, delirium, occasionally (when a 'substance' is put in her drink by Lily) euphoria, and finally full-on homicidal madness. I couldn't discern reality from fantasy in this film, which is something that excites me and surprises me. That it's also in the framework of a full-borne melodrama is something that excites further. No, it's not quite The Red Shoes. It's something different, adaptive, as if Stephen King with a refound lust for glory took the Red Shoes and doused it in kerosene and made it dance till it passed out. It's script, which deals in conventions, is deceptive once its truer purposes are revealed by its director (who, admittedly, rises it up from potential pitfalls that backstage-dramas can have).

Casting is so important though, outside of a director's vision, and Aronofsky has a lead here that could equal her previous Randy 'The Ram' from The Wrestler. Natalie Portman seems to find a really strong role every five years or so, and this is one of them. In Nina she finds darker countours than I've seen her play before, and as the filmmaking reaches a feverish pitch the actress is right there along for the ride. I mentioned close-ups before (as did Jim Emerson in his blurb, bless him), and Portman is game to fill up the frame with her availability and horror that she can give as an actress. It's a revelatory performance in that she runs a gamut of emotional notes from tender to sad to hysterical to mad to evil and just downright... determined. That she's also an amazing ballerina should be a given to be in this film, though her dedication to the role pays off in that climactic Swan Lake performance. It's not all visual fx up there and lighting daring-do. It's flesh and blood and eyes turned red and wings flapping like daggers.

Did I mention the music? Or the cinematography? Or any number of things? In short, it's one of the best of the year, do go see it if it's around the area or when it opens wider this Christmas. As far as head-trip mind-fuckers go, it's the director's finest and, within its cozy hand-held 16mm confines, most ambitious work.

Friday, December 10, 2010

The Disputed Truth: Inside Job

by Jack, Jon, & Matt

Jack and Jon have some things to say about Charles Ferguson financial expose Inside Job, and they aren't shy about saying them. Matt tries to keep the peace while they get to bottom of what the film does right and what it does wrong.

**CLARIFICATIONS & CORRECTIONS**

4:17 clarification: Glenn Hubbard was Chief Economics Advisor under George W. Bush, current Dean of Columbia Business School, and one of the masterminds behind Bush's controversial tax cuts. When director Charles Ferguson asks him to disclose some of the companies he's consulted with, in case of conflict of interest, he compares the line of questioning to a deposition, says agreeing to be interviewed was a mistake, and challenges Ferguson to “give it your best shot!”

4:59 clarification: Jack cites an NPR interview with Ferguson, which can be found here.

6:27 correction: Jon asserts that Ferguson cuts away from interviews throughout the film while his subjects are still formulating their answers. In fact, he only does this twice. He does, however, often include only incomplete answers, sometimes for the sake of brevity or apparently to prevent the subject from backing up their assertions. As Matt and Jack state later in the podcast, virtually all documentaries of this type do this to varying degrees. The same cannot be said for the multiple instances in which Ferguson gives himself the final word during the interviews, undercutting his subjects and not allowing them to rebut him.

7:29 clarification: Matt refers to an instance in Fahrenheit 9/11 in which director Michael Moore questions Representative Mark Kennedy on his way into the Capitol. Kennedy's entire response, during which he reveals information contrary to Moore's implication, is cut from the film. This is not an entirely valid analogy. To our [the Stumped staff's] knowledge, none of Ferguson's subjects have accused him of such a blatant misrepresentation (at least not publicly). Moore has since released a transcript of his response, which can be found here.

10:14 clarification: Jack asserts that Charles Ferguson has a background in government. Though he never held public office, he is a doctor of political science and has consulted with many federal offices, including the White House.

10:48 correction: Jon challenges Jack to name a single economist interviewed in the film, suggesting that the film's economic perspective comes from business professors and CEOs. Jack fails to do so, but in fact, most of the film's subjects have backgrounds involving economics. Examples include Daniel Alpert, Sigridur Benediktsdottir, Willem Buiter, John Campbell, Satyajit Das, Martin Feldstein, Glenn Hubbard, Simon Johnson, Christine Lagarde, Andrew Lo, Frederic Mishkin, Charles Morris, Raghuram Rajam, Kenneth Rogoff, Nouriel Roubini, Paul Volckner, Martin Wolf, and Gylfi Zoega. All of these individuals (along with other of the film's subjects, to varying degrees) have had some involvement in the study of economics (which is a social science involving statistical analysis in the study of market trends and their effects over time), be it as a journalist, an advisor, a professor, a researcher, or a public official. The term might even apply to Ferguson himself, who has published papers, written books, given lectures, and now directed a feature film on economic subject matter. Jon is correct in his assertion that economics and business are distinct fields, but they are not mutually exclusive. Some of these economists have gone on to hold positions in business schools, which is probably where the confusion arose. The film itself also spends a great deal of time exposing how businessmen and CEOs have been afforded undeserved authority as economists by media, universities, and government officials, even discrediting some of its subjects by this principle.

14:18 clarification: Without access to the graphs themselves, we have so far been unable to judge the accuracy of Jon's statements on the film's use of graphs and their inclusion of inflation prices. Typically the farther back the data goes, the more necessary such adjustments become. Inside Job deals primarily with data from the past ten years, so inflation is a minor variable in most cases.

20:04 clarification: Matt cites similarities between Ferguson's directing style and that of fellow documentarian Alex Gibney. Fun fact: Gibney was a consultant on Ferguson's Oscar-nominated debut, No End in Sight.

22:07 clarification: Jon asserts that many companies require the use of private jets, so the film's criticism of AIG's jet fleet is unjustified. This is true of many companies, but AIG is not one of them. Since the bailout of the auto industry, use of private jets has gone down, and AIG has decreased its fleet. Despite their association with corporate decadence, private jets do serve many practical functions. For instance, they speed up transit by bypassing the convoluted process of commercial airlines, they guarantee the company control over the flight, and they act as a mobile office so executives don't lose any time from their busy schedules. This is at a much greater cost, so the worth of this trade-off is debatable.

22:50 clarification: Jon suggests that the film unduly criticizes Lehman Brothers for not notifying French Finance Minister Christine Lagarde about their impending collapse. This is a misunderstanding of that sequence. Hank Paulson and Ben Bernanke were negotiating a deal for the takeover of Lehman Brothers, but neglected to inform other governments of the disaster on the horizon. They break no laws by their silence, but the shock expressed by Ferguson, Lagarde, and Jon's fellow viewers is very justifiable, given that her close associates failed to warn her of the meltdown (especially after she had personally voiced concerns to Paulson months earlier).

Jack and Jon have some things to say about Charles Ferguson financial expose Inside Job, and they aren't shy about saying them. Matt tries to keep the peace while they get to bottom of what the film does right and what it does wrong.

**CLARIFICATIONS & CORRECTIONS**

4:17 clarification: Glenn Hubbard was Chief Economics Advisor under George W. Bush, current Dean of Columbia Business School, and one of the masterminds behind Bush's controversial tax cuts. When director Charles Ferguson asks him to disclose some of the companies he's consulted with, in case of conflict of interest, he compares the line of questioning to a deposition, says agreeing to be interviewed was a mistake, and challenges Ferguson to “give it your best shot!”

4:59 clarification: Jack cites an NPR interview with Ferguson, which can be found here.

6:27 correction: Jon asserts that Ferguson cuts away from interviews throughout the film while his subjects are still formulating their answers. In fact, he only does this twice. He does, however, often include only incomplete answers, sometimes for the sake of brevity or apparently to prevent the subject from backing up their assertions. As Matt and Jack state later in the podcast, virtually all documentaries of this type do this to varying degrees. The same cannot be said for the multiple instances in which Ferguson gives himself the final word during the interviews, undercutting his subjects and not allowing them to rebut him.

7:29 clarification: Matt refers to an instance in Fahrenheit 9/11 in which director Michael Moore questions Representative Mark Kennedy on his way into the Capitol. Kennedy's entire response, during which he reveals information contrary to Moore's implication, is cut from the film. This is not an entirely valid analogy. To our [the Stumped staff's] knowledge, none of Ferguson's subjects have accused him of such a blatant misrepresentation (at least not publicly). Moore has since released a transcript of his response, which can be found here.

10:14 clarification: Jack asserts that Charles Ferguson has a background in government. Though he never held public office, he is a doctor of political science and has consulted with many federal offices, including the White House.

10:48 correction: Jon challenges Jack to name a single economist interviewed in the film, suggesting that the film's economic perspective comes from business professors and CEOs. Jack fails to do so, but in fact, most of the film's subjects have backgrounds involving economics. Examples include Daniel Alpert, Sigridur Benediktsdottir, Willem Buiter, John Campbell, Satyajit Das, Martin Feldstein, Glenn Hubbard, Simon Johnson, Christine Lagarde, Andrew Lo, Frederic Mishkin, Charles Morris, Raghuram Rajam, Kenneth Rogoff, Nouriel Roubini, Paul Volckner, Martin Wolf, and Gylfi Zoega. All of these individuals (along with other of the film's subjects, to varying degrees) have had some involvement in the study of economics (which is a social science involving statistical analysis in the study of market trends and their effects over time), be it as a journalist, an advisor, a professor, a researcher, or a public official. The term might even apply to Ferguson himself, who has published papers, written books, given lectures, and now directed a feature film on economic subject matter. Jon is correct in his assertion that economics and business are distinct fields, but they are not mutually exclusive. Some of these economists have gone on to hold positions in business schools, which is probably where the confusion arose. The film itself also spends a great deal of time exposing how businessmen and CEOs have been afforded undeserved authority as economists by media, universities, and government officials, even discrediting some of its subjects by this principle.

14:18 clarification: Without access to the graphs themselves, we have so far been unable to judge the accuracy of Jon's statements on the film's use of graphs and their inclusion of inflation prices. Typically the farther back the data goes, the more necessary such adjustments become. Inside Job deals primarily with data from the past ten years, so inflation is a minor variable in most cases.

20:04 clarification: Matt cites similarities between Ferguson's directing style and that of fellow documentarian Alex Gibney. Fun fact: Gibney was a consultant on Ferguson's Oscar-nominated debut, No End in Sight.

22:07 clarification: Jon asserts that many companies require the use of private jets, so the film's criticism of AIG's jet fleet is unjustified. This is true of many companies, but AIG is not one of them. Since the bailout of the auto industry, use of private jets has gone down, and AIG has decreased its fleet. Despite their association with corporate decadence, private jets do serve many practical functions. For instance, they speed up transit by bypassing the convoluted process of commercial airlines, they guarantee the company control over the flight, and they act as a mobile office so executives don't lose any time from their busy schedules. This is at a much greater cost, so the worth of this trade-off is debatable.

22:50 clarification: Jon suggests that the film unduly criticizes Lehman Brothers for not notifying French Finance Minister Christine Lagarde about their impending collapse. This is a misunderstanding of that sequence. Hank Paulson and Ben Bernanke were negotiating a deal for the takeover of Lehman Brothers, but neglected to inform other governments of the disaster on the horizon. They break no laws by their silence, but the shock expressed by Ferguson, Lagarde, and Jon's fellow viewers is very justifiable, given that her close associates failed to warn her of the meltdown (especially after she had personally voiced concerns to Paulson months earlier).

Thursday, December 9, 2010

Inside Job review

by Matt

Remember all that stuff I said about how difficult Disney writers have it? The same thing goes for feature-length documentary filmmakers, only double it. When it deals with politics, square it. When Michael Moore is involved, add another exponent for every year since Roger & Me.

You not only have to convey accurate, factual information which satisfies the critical viewers who will comprise much of your audience, but you must also make the information compelling, weaving it into the fabric of a story. If you fail at one, the other will suffer. I feel this is the case with Inside Job.

It should all be there: political and white-collar corruption, an industry whose success is based on the very source of its eventual downfall, larger-than-life personalities exploiting an establish they themselves control. Scorsese would have a field day.1 Instead, the film spends most of its time interrupting its uninteresting interview subjects so director Charles Ferguson can butt in with his two cents or Matt Damon can reiterate with intense narration.

The choice of Matt Damon as narrator puzzled me as I watched the film. I would never argue that Mr. Ripley isn't talented (badump tish!), but his voice doesn't carry the same fatherly authority as a Peter Coyote (Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room) or Morgan Freeman (Morgan Freeman, duh!), nor the unassumingness of Josh Brolin (The Tillman Story). We recognize him immediately as the voice of countless spies, con men, and depressed mathematicians.

Usually, in a film like this, the narrator is the main drive with the interviews highlighting his points with details and anecdotes. Too often, the interviews simply reiterate Jason Bourne's previous statement or vice versa. What works in the trailer to Black Dynamite doesn't necessarily work everywhere else.

Come to think of it, much of the editing was pretty shoddy. The interview subjects always seem like they're being cut off in the middle of a thought. As I said to Jon during our podcast, it isn't uncommon for interviews to be truncated like this, but after seeing the film, I must concede that the cuts don't usually draw attention to themselves like they did here. The animations likewise tended to be very drab, simply sitting there on the screen with their smug little arrows and legends. On top of this, at least one of the interviews had a noisy lavalier microphone which kept shuffling against the subject's clothes. I can't help but resent a serious Oscar-contender that shows less attention to detail than most freshman film students.

These complaints might seem beside the point, but I don't think they are. The content of a film cannot be judged apart from its style. They are woven together. Individual elements might seem to play well enough (the heist movie opening credits sequence, the shocking congressional hearings, Elliot Spitzer's "Do I seriously have to talk about my affair again?" reaction, Ben Affleck's monologue about wanting a better life for Will), but if they can't form into a coherent whole, the film doesn't work.

Go back and listen to the podcast (we need the hits), and look at the clarifications page. The aesthetic mishandling of this information actually leads Jon to several erroneous conclusions about the truth of the film's claims. Had the film been directed with greater cohesion, had it a more focused point of view, had Ferguson actually demonstrated any interest in his subjects during the interviews, I doubt this would've been the case.

Inside Job has probably had more universal renown than any other non-fiction film in a year dominated by documentary masterpieces. It is well-researched, hard-hitting, and will be an eye-opener to most of its viewers. I dispute neither its facts, figures, or conclusions. I only wish I had gotten them from a more compelling film.

1 - Marty, if you're reading, make it happen! You can put Matt Damon in it!

P.S. Matt Damon, if you're reading this, please don't take it too personally. I really do enjoy your work. You were great in Inception.

Remember all that stuff I said about how difficult Disney writers have it? The same thing goes for feature-length documentary filmmakers, only double it. When it deals with politics, square it. When Michael Moore is involved, add another exponent for every year since Roger & Me.

You not only have to convey accurate, factual information which satisfies the critical viewers who will comprise much of your audience, but you must also make the information compelling, weaving it into the fabric of a story. If you fail at one, the other will suffer. I feel this is the case with Inside Job.

It should all be there: political and white-collar corruption, an industry whose success is based on the very source of its eventual downfall, larger-than-life personalities exploiting an establish they themselves control. Scorsese would have a field day.1 Instead, the film spends most of its time interrupting its uninteresting interview subjects so director Charles Ferguson can butt in with his two cents or Matt Damon can reiterate with intense narration.

The choice of Matt Damon as narrator puzzled me as I watched the film. I would never argue that Mr. Ripley isn't talented (badump tish!), but his voice doesn't carry the same fatherly authority as a Peter Coyote (Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room) or Morgan Freeman (Morgan Freeman, duh!), nor the unassumingness of Josh Brolin (The Tillman Story). We recognize him immediately as the voice of countless spies, con men, and depressed mathematicians.

Mark Whitacre records his narration for Inside Job

Usually, in a film like this, the narrator is the main drive with the interviews highlighting his points with details and anecdotes. Too often, the interviews simply reiterate Jason Bourne's previous statement or vice versa. What works in the trailer to Black Dynamite doesn't necessarily work everywhere else.

Come to think of it, much of the editing was pretty shoddy. The interview subjects always seem like they're being cut off in the middle of a thought. As I said to Jon during our podcast, it isn't uncommon for interviews to be truncated like this, but after seeing the film, I must concede that the cuts don't usually draw attention to themselves like they did here. The animations likewise tended to be very drab, simply sitting there on the screen with their smug little arrows and legends. On top of this, at least one of the interviews had a noisy lavalier microphone which kept shuffling against the subject's clothes. I can't help but resent a serious Oscar-contender that shows less attention to detail than most freshman film students.

These complaints might seem beside the point, but I don't think they are. The content of a film cannot be judged apart from its style. They are woven together. Individual elements might seem to play well enough (the heist movie opening credits sequence, the shocking congressional hearings, Elliot Spitzer's "Do I seriously have to talk about my affair again?" reaction, Ben Affleck's monologue about wanting a better life for Will), but if they can't form into a coherent whole, the film doesn't work.

Go back and listen to the podcast (we need the hits), and look at the clarifications page. The aesthetic mishandling of this information actually leads Jon to several erroneous conclusions about the truth of the film's claims. Had the film been directed with greater cohesion, had it a more focused point of view, had Ferguson actually demonstrated any interest in his subjects during the interviews, I doubt this would've been the case.

Inside Job has probably had more universal renown than any other non-fiction film in a year dominated by documentary masterpieces. It is well-researched, hard-hitting, and will be an eye-opener to most of its viewers. I dispute neither its facts, figures, or conclusions. I only wish I had gotten them from a more compelling film.

1 - Marty, if you're reading, make it happen! You can put Matt Damon in it!

P.S. Matt Damon, if you're reading this, please don't take it too personally. I really do enjoy your work. You were great in Inception.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)